Hey folks!

I gotta say, the last two days have held some of my most exciting and best photographic moments. What’s the secret? Getting out there! As a photographer, if you don’t make the effort, you don’t get the shots. To shoot an animal truly as it is, to capture its essence or some fantastic behaviour in a photograph, you have to have two key skills:

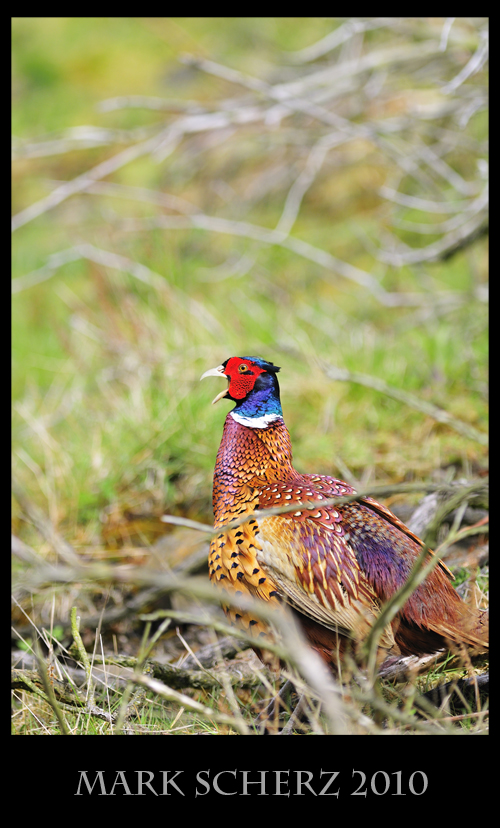

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/640s f/2.8

The first, is to know the animal. Without knowledge of the animal, you will not be able to find it, and capture it on digital film. This isn’t something that you just have. You have to go out there, be with the animal, in its habitat, follow it around, learn, study, watch.

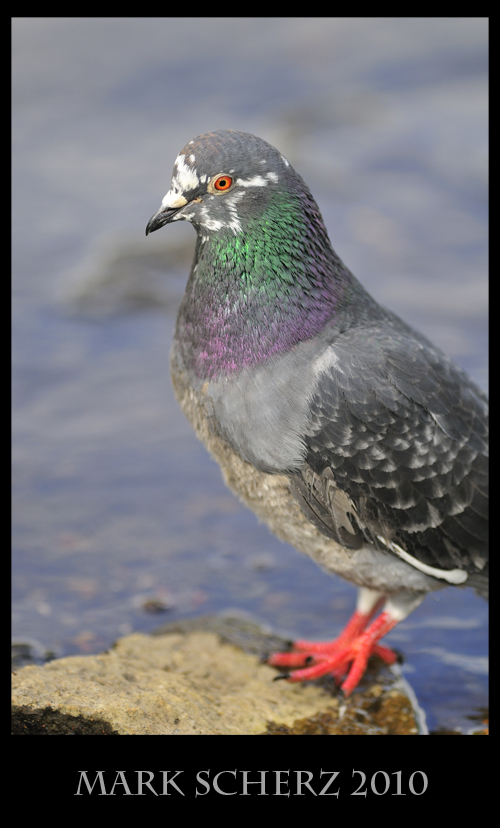

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/500s f/2.8

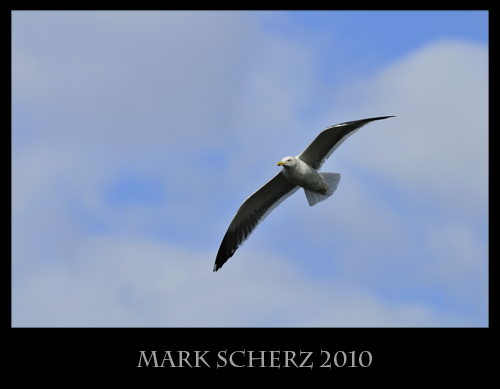

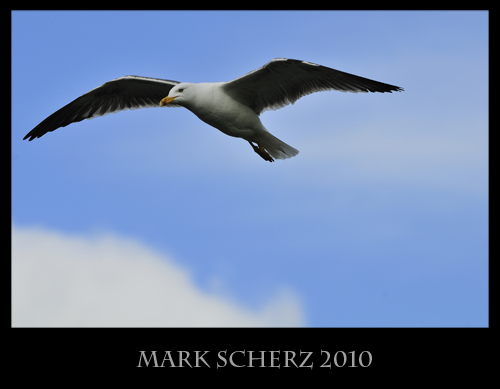

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/3200s f/2.8

I have so little experience, but by just following pheasants for hours at a time, I learned to watch for behavioural patterns.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/800s f/6.3

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/2500s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/3200s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/2000s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/2000s f/2.8

I learn something new with every minute spent with these fantastic creatures. I learn to push boundaries, to recognise something before it happens, and, most importantly, I learn what makes these birds what they are – something about their character.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/2000s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/2500s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/1600s f/2.8

So what does it take to learn the behaviour of an animal like this? To be able to take shots that capture it? Time, patience, and a keen and observant eye. You have to know when not to click – a growing issue with modern digital film, and one that I am still working on. And most important of all, you’ve gotta wanna. Without the wanna, you won’t be able to have the patience. It’s the drive that pushes you to get that picture, and to push those boundaries, and learn from your mistakes. If you’re too hasty, you lose the shot. If you’re too slow, you miss the shot. Either way, you learn.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/800s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/1600s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/1600s f/2.8

Remember also, as a wildlife photographer, you are a biologist and a lucky observer before – and I stress this because it is an important issue to me – before you are a photographer. Relish in the priveledge of observing the wildlife, and do your utmost to avoid undue disturbance. This not just because a disturbed animal will not behave naturally, but also because you are intruding on its home, and that demands respect.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/1600s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/1250s f/2.8

What then is the other element? Well, I would call it “conditions”. Without the light, you miss the shot. Without a nice background, the shot is crummy. With a messy foreground, you might as well forget about it. But there are things about the conditions that are dependent, not on Mother Nature and Her love of screwing with things, but on YOU, the photographer. If YOU know your gear, know how to wield it well, you can make the most of conditions that are against you.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/320s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/400s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/500s f/2.8

Now you know I’m a gearhead – I will freely admit that I have a problem with that, but that does not at any length mean that I don’t know my gear and how it works under different conditions. Granted I learn every time I’m out, but that never stops me from knowing when to use what.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/5000s f/8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/100s f/9

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/800s f/2.8

I know, before I walk out the door, whether or not I should have a teleconverter on, just by looking outside. When I get to shooting the animals, I know immediately if it was a mistake to put it on, and, if possible, I’ll take it off – and I learn. I know immediately if I have the wrong lens for a task, and, weather permitting, I will change it to get the shot. I know what angle I can push when shooting against the sun with the 300mm VR, and I know how it behaves when I’m panning on a flying bird. You have to know what your gear can deliver under every set of circumstances, and how it will respond to you pushing it to get that shot.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/8000s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/2000s f/5

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/1250s f/8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/640s f/8

Again, what does it take to do this? To learn to use your gear as an extension of yourself? Time! Time behind the lens teaches you more about it than any other activity can. I read blogs obsessively (and I encourage you to do so too), and I learn everything I can about a lens before I take it out – but that’s a bad habit! There is no substitute for practice when it comes to your photography. Remember that your camera is like an instrument. Push the buttons right, and you get a beautiful image; push ’em wrong, and you get squat. It comes down to you producing the images, and if you get an amazing opportunity and screw it up, you have only yourself to blame.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/8000s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/800s f/8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/6400s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/4000s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/8000s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/400s f/8

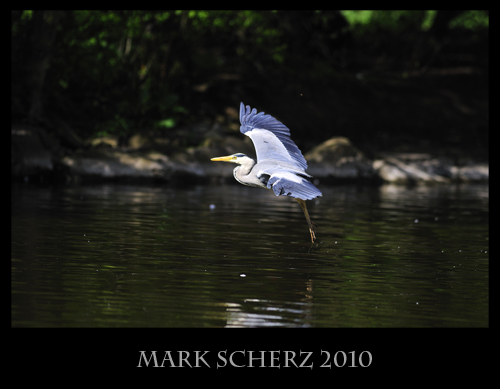

Make an effort, go out, sit down at the side of a lake with your camera – I did yesterday, and in the two hours I was sitting there, I got several hundred shots, and of those, only a handful were keepers. But of the keepers, some of them were just magestic.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/3200s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/2000s f/2.8

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/640s f/6.3

The rewards, well, they speak for themselves really. So go out, sit down, and learn something about your local biology. Study a rabbit community, learn to recognise bird song, follow a pheasant, and you’ll be surprised at how it improves your photography.

D300 + 300mm VR @ 1/800s f/6.3

And when you’ve done that, share them! I’d love to hear about what you’re shooting, see your images, and help with anything I can! I’ve got a flickr account (over on the right bar) and this website has it’s own Facebook Fanpage where you can follow the blog and hear from me. Finally, I’ve also got a Twitter, where you can hear more about what’s going on in my photography. You can share your work through any or all of these!

I look forward to hearing from you! Go shoot!

Hey Mark,

wonderful shoots, and after reading, i feel encouraged to do more and better photography than actually.

Go on!

Mark, I really love all of the pheasant ones 😀

Hmmm…. I used to do a lot of zoo photography, I also do wildlife photography in the field. There are those photographers who apply field techniques to zoos (I’m one of them). I have, for instance, been known to sit at a specific enclosure (usually the primates or big cats) waiting for a truly unique or particular photo ALL DAY. Often I have come home with nothing to show for my endeavours, but I do take your point.

As for zoos, I see them as a necessary evil. Most of them use a portion of their profits to research in the field and they do educate the public who visit the zoo. It’s the only way for many people to see exotic animals in the flesh, and if that gets people caring about the plight of these animals then there is some good to it. But again, I do see your point of view. I would much rather be out in the field with my photography (I am off looking for Great Crested Grebes next week), but I also enjoy my foray into zoo photography when I get the chance.

I know what you mean about the application of field techniques. I do that often when I’m going to zoo for the sake of my own photography, but that is so rare now that it’s almost irrelevant to my personal photography. I know of several photographers who spend hours upon hours in zoos, waiting for some KILLER photos. Still, I would take a day in a forest over a day sitting outside an enclosure any day.

I envy you greatly the Crested Grebes! I have only ever seen two or three in the wild. I have no idea where to find them in Scotland, so I shall have to do some research. In fact, they may even be found in Switzerland; I’m not really sure. I have seen some stunning photography of them. I don’t know if you know of http://imagesfromtheedge.com/blog/ ? Just a few weeks ago there was a gorgeous post of Grebes. I will definitely look into that. I’d love to see and shoot some.

Thanks for the link, I shall certainly check that out. I have been moving away from zoo photography myself over the last year or so. I have been shooting landscapes mainly, but I really would love to get back into the field and start shooting real wildlife in their natural environments again. The Grebes are a start, but there’s also an RSPB reserve 10 minutes fro where I have moved to, so I may be spending a bit of time down there.