Fort Dauphin

Fort Dauphin has a strange atmosphere to it. It is as though its history of great touristic and industrial activity has vanished, leaving behind what is, in places, almost a ghost town. It is eerily quiet, outside of the marketplace, and the beautiful hotels which rise above the town stand empty and forgotten. The tourist season didn’t really happen this year – the economic crises appears to be reflected in the pockets of the rich globe trotters. Finished are the days where the vazaha (white person/foreigner) dominated the streets, and the tourist boutiques made a booming trade. What remains is the shell of a town that relied, at least in part, on foreign money. The poor areas have remained desolate, while the richer areas have simply ceased to prosper. Half finished hotels stand crumbling on the shore. This is not the first poor tourist year, nor will it be the last.

For us, the lack of tourists meant that we received all of the attention from street sellers – a pain and a half when you are not interested in buying any of their produce. But they see you as a rare opportunity, and will literally follow you for miles (one poor soul followed us for about two kilometres, before giving up – and he was back the next day!).

We had the advantage that we were staying with the family-in-law of our translator, Junassye, whilst in Fort Dauphin – this decreased the prices incredibly. Still, with nowhere to cook, our food bills were immense – food in FD costs twice at least what you pay in Tana.

We spent quite a while in Fort Dauphin. Just a few days on the way in, but five on the way out. On the way in, we were busy getting our gear together in preparation for the field, meeting with relevant authorities, and of course getting to know the Centre Ecologique de Libanona (CEL) students we were working with. Then, on the way out, processing data and meeting with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). We also gave a talk to students in the School for International Training (SIT), who are based in CEL for the duration of their time in Madagascar.

On the Road

The trip from Fort Dauphin to Kobokara is about 5 hours by 4×4 – 136 kilometres, according to my GPS. For the first leg of the journey out, you drive through rice patties and hills, now bare, but once covered in rainforest. When you see them at this scale, you do not get to comprehend the heartbreaking reality of the amount of forest that has been felled across the island – they just look like bare, grass covered hills, like you might see in Europe.

It is only when you see the stumps of the enormous trees that once were there that you get an idea of the scale of the forest that once was.

It is here too that the fruit markets stop, for the growing of fruit is not something that goes particularly well on the western side of this border.

You transition quite quickly from the eastern rainforest belt, over to the dry, spiny forest. At first it is a bit of lessening of the green, and then suddenly there are enormous octopus trees and thorny shrubs on either side of the vehicle.

The expanse of spiny forest is broken only by the hundreds of miles of sisal plantations, and places where prickly pear has taken over, for prickly pear is probably almost as bad for the local forests as the actual sisal plantations – it is massively invasive, and in places the forest that it has taken over is no longer recognisable as spiny forest at all. Its use of course is that of food; the fruit feed people and goats, the flesh feeds cattle and also tortoises – it is useful, but it comes at the price of the forest it extinguishes.

Kobokara

There is a particular magic to Kobokara. We were treated in true African style, as honoured guests, but there was more to it than that; the family bonds run so strongly through the people, we were closer to treasured family than guests – a true honour. Because we were living so close to the people, we became part of their routines, and our own provided a source of constant amusement.

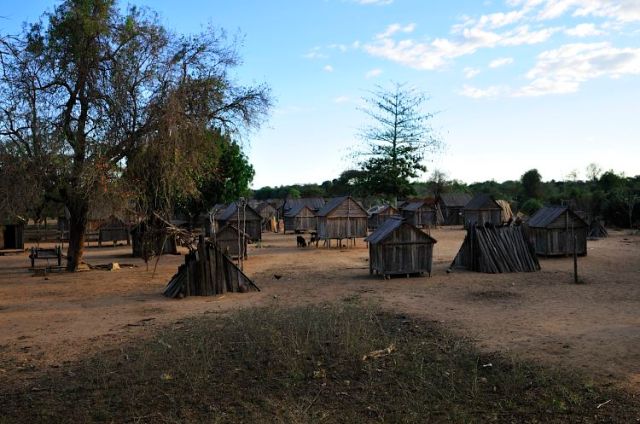

Home for the team for two months - this massive tree stands in the middle of our family's area of Kobokara.

Most of the village is composed of houses made from hand crafted planks of wood, though larger houses are made of brick. It costs approximately £60 to build a house of bricks, and significantly less to build it of wood.

Bricks being made for the expansion of a house - £20 for the whole job, including labour and materials.

The houses are typically furnished with shelves, a bed, and various hanging places for all of the clothes. Usually, the floor is covered in reed matts, which provide a smooth surface on the feet. Light is provided either through candles, which are expensive, or not at all – rising with falling with the sun is typical, so light inside is not always needed at night. The moon fortunately is bright enough for most of its cycle to cast shadows at night, providing illumination when it is needed, to get to places. But they are not without technology – before we arrived, there were already at least two wind-up torches that I am aware of, and our guide had a battery powered torch. In fact, torches are readily available at the weekly market – they have three settings: spot torch, soft torch, and disco. The disco function provided for some very memorable evenings.

Society is powerfully divided between the sexes. The men sort all of the official business and tend to the goats and zebu, while the women do everything else, from washing to cooking to feeding chickens to cleaning. Polygamy is commonplace, and though the first wife of a man is allowed to yay or nay the second wife (I imagine she doesn’t actually get that much say), if she is unfaithful to her husband, she can be shot. Of course, there are some men who break the mould and are happy to be together with just one woman. Still, it is interesting that Christianity has influenced so much, including local beliefs and language, but it fell short when it came to monogamy.

One strictly male profession is to drive and look after zebu carts – arguably the best mode of transport in the world, if a little uncomfortable, and riddled with zebu droppings. Their design is similar to european ox carts, though the materials are much lighter and smaller. Communication with the zebu happens in a special language, combined with clicks and trills. Oh and a thorny branch in the tenders.

The setting could scarcely be more stunning. The river runs alongside the village (500m wide I would estimate the basin to be, though the flow is only maybe 40m), and is, I think, the only reason these people are still able to live here. Even when the river is dry, there is water to be had in the basin. That means that there is food, and the people are able to prosper, despite the water being less than clean.

One of the things Justine (one of the anthropologists on my team) set out to do was to teach a bit of english, and form a connection with Simpson’s Primary School in the village. This she achieved wonderfully. Part of this project was to create a sign, which the children in Simpson’s Primary School designed:

When finally it came time to leave, we gave away about 60% of our items (including things we did not really want to part with!) – it is much easier to travel when you don’t have a load of crap with you. This created an enormous bustle of activity in camp. Almost unbearably insane on the last day. But it was a great way to leave it – everyone happy, and us leaving knowing we kind of enriched peoples lives with goodies.

The last day - everyone grabbing what they can, even things apparently useless, both to us and them.

Antananarivo

We stayed with a friend, Harimalala. This meant that we had someone who knew what they were doing, we didn’t have to pay for a hotel, and we got to cook, so we saved a shedload of money that way. Tana’s restaurants are generally cheap, but the market is infinitely cheaper, unless of course you are white, at which point tomatoes apparently cost 5000 ariary for 5 – I actually snorted when someone said this to me. 200-300 ariary is the actual price. At a busy market in Fenarivo, the local market in market for us in Kobokara, the rain drove tomatoes into season, and their price dropped to 100 ariary for 9 or so. Harimalala’s flat is bright green. That’s the best thing about it. It made for fun pictures.

Madagascar’s capital has a unique feel to it. The hustle and bustle is crazy. Taking a bus (a converted van usually, with a guy who stands on the back, opening the door and collecting the fee to ride the bus of 300 Ariary – 10p per person in UK money, and seats that are too close together for my legs to fit behind) is the best way to get an idea of the sprawl and size of Tana. It streches on for miles – a population of just over a million people, living in a town where 99% of the buildings are one or two stories tall (Madagascar is the only place in the world where I have ever seen two story mud huts). There are of course a few buildings which are taller, but those are all located in the city centre, and next to the airport.

I do not, by the way, recommend taking a bus in Tana unless you have someone with you who knows what they are doing, or speak Malagasy yourself. Two buses with the same plaque on the front may go to completely different places, or the same place but by different routes. I never did work out how Harimalala knew which bus was going where. Also, in rush hour, the queues in the dedicated bus stopping places can strech for hundreds of metres, and I imagine some people literally do stand all night waiting on a bus.

The city is built around rice patties, which strech for miles, bordered by buildings on all sides, and interspersed with tiny island villages. Unfortunately these rice patties lead to a mosquito problem, which makes it almost unbearable at night. The setting could scarcely be more spectacular though.

That’s all for this post. Keep your eyes out for the next – Football!

very very very nice!

great:D

Thanks Xandi, and thanks for subscribing 🙂

Hi, I just read an article about the drought in Kobokara in the latimes.com. They haven’t had rain in three years and two of the mothers interviewed said they had no money for food let alone water. I feel compelled to ask you how do I go about helping the less fortunate in this village directly? I read the study that your expedition did to Kobokara and was dismayed at the fact that the “wealthy” and their immediate families continued to get money from being employed by your group. I need to understand how to send cash to these women and their children. Do you have any thoughts on how this can be achieved? I have tried to google my questions but it gave no answers. I would appreciate any help you can offer.